Trying To Make A Difference: From Private Practice to Community Justice

Author: Tiffany Lu

Interviewers: Nishara Fernando, Nelson Thomason & Tiffany Lu

Paul Were takes us behind the scenes of elder abuse law, revealing the realities and challenges of protecting vulnerable older adults. From managing the elder abuse teams at the Eastern Community Legal Centre to leading community education workshops, Paul shows us the profound impact of community-based legal work.

Chapter 1: Change of Plans

Like many of the lawyers EncycLAWpedia has interviewed, Paul did not initially set out to pursue a career in law. He started university studying business and only towards the conclusion of his degree, decided to add law into the mix—a decision that quickly grew into a genuine passion and led him to complete a Master of Laws. Reflecting on that journey, Paul encourages students not to feel pressured to map their career out from day one. ‘Sometimes students feel that there's a need to know exactly what you want to do, or that if you're studying law, you need to want to be a lawyer afterwards. But, there are heaps of people who are doing absolutely awesome things with their law degree, but it's not necessarily working as a lawyer.’

Chapter 2: Finding His Calling

Paul’s progression into the Elder Abuse space came through his work in private practice. As a graduate and later a lawyer at Eastern Bridge Lawyers, Paul was introduced to Wills and Estates, which gave him a glimpse into the troubling realities of elder abuse. ‘I'd sometimes see things like pressure from kids to transfer money, to give inheritance before the older adult had died. There'd be pressure to sign documents, to be a guarantor on a loan, or to allow someone to become an attorney under a power of attorney for them so they had control over that person's money.’

Supported by the client-forward culture of the firm, Paul learnt to push back against these forms of abuse. So when a dedicated Elder Abuse Lawyer position opened up at the Eastern Community Legal Centre (ECLC), it felt natural for Paul to transition into a more specialised role. Paul reflects on the shift from private practice to community legal work as eye-opening. At the ECLC, services are completely free, keeping the focus on supporting clients without concern for billable hours. This environment fostered a culture of dedicated, client-centred advocacy that Paul found aligned with his values. He has been working at the ECLC for five years now and is currently the centre’s Managing Lawyer for elder abuse.

Chapter 3: The Tough Realities

As a Managing Lawyer, Paul oversees two elder abuse programs at the ECLC: Engaging and Living Safely and Autonomously (ELSA) and Rights of Seniors in the East (ROSE). These response teams provide free legal, social, and financial assistance to older people experiencing or at risk of elder abuse.

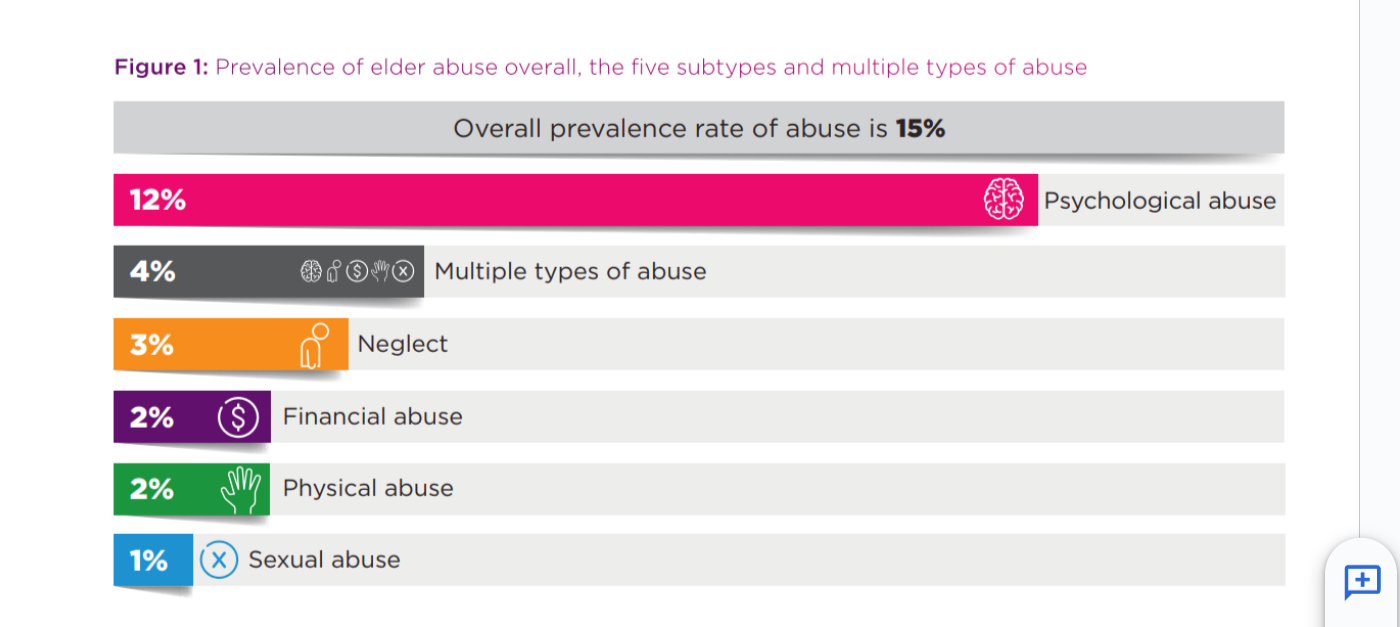

Most often, clients come to these services after facing financial or emotional abuse. Financial abuse, Paul explains, might look like someone taking money from an older person’s bank account, transferring property into their own name, or even running up credit card debt in the older adult’s name. Emotional abuse generally involves manipulation, pressure, or the perpetrator making the older adult feel unsafe. Candidly, Paul shares that emotional abuse appears in ‘probably every file’ that crosses the ECLC’s desk.

The ELSA and ROSE teams also handle cases involving physical or sexual abuse or neglect, though these forms of abuse are less frequently reported. ‘It's more prevalent in the community than we actually see at our service because a lot of the time, when people experience neglect, they're unfortunately not in a situation to get legal help for one reason or another. So that's really tricky.’

Outside of work hours, Paul often leads community education sessions to raise awareness about elder abuse and share practical tips on how to prevent it, as well as highlighting the services the ECLC provides.

Sourced from the National Elder Abuse Prevalence Study Summary Report.

Chapter 4: The Impossible Predicament

According to the National Elder Abuse Prevalence Study Summary Report, 18% of elder abuse is committed by an adult child. Paul is surprised by this figure as the ECLC sees closer to 60% of their files involving abuse by adult children.

Paul describes these situations as the Impossible Predicament—where an older person ‘feels stuck and can’t tolerate the abuse they’re experiencing, but because of their close relationship with the perpetrator, they don’t feel that they can take any steps to prevent that abuse from happening in the future.’ As a parent himself, Paul empathises with this dilemma. He stresses the importance of client autonomy; his team’s role is ‘to encourage people to take legal action if they're comfortable with it, but not force them to do it if they don't want to.’ In many cases, the most that can be done is to explain the available legal options and leave the decision with the client.

Paul shares that the greatest difficulties come when the client has lost the capacity to give instructions about legal matters. ‘We might see that abuse is happening, but unfortunately, if they’re not able to understand all the different issues that are happening or the implications of their actions, or the legal advice that we’re giving, we’re often stuck and unable to assist them further.’

While the job does come with its challenges, the work remains deeply rewarding. ‘Something I find really fulfilling is that the outcome, whether it's them getting a large sum of money back or being protected—this wouldn't have happened if our service didn't exist.’

Chapter 5: Support for the Supporters

Naturally, working in elder abuse law comes with its own emotional tolls. ‘We're often hearing really difficult stories and seeing challenging things,’ Paul explains. ‘It’s really common that we will be worried about clients even outside of work.’

What makes all the difference is the support systems integrated into the workplace. The ECLC hosts Reflective Practice Sessions, during which the team comes together to share challenges at work and strategies for addressing them. ‘I think that’s really a critical part of it because it means that not only do we talk about those specific things, but also we get insight into how other people are feeling and how they’re managing stress, which is equally important.’ Staff may also access a private Employment Assistant Program for one-to-one support and counselling. These systems, Paul believes, are vital to sustaining lawyers in this emotionally heavy field.

Safeguarding elders’ rights, dignity, and wellbeing

Chapter 6: Paths Into Practice

For students curious about this elder abuse law, Paul offers both encouragement and realism. While funding and roles may not be as plentiful as in other sectors, opportunities do exist for those passionate about the cause. Gaining experience is, in his view, the best way to stand out. His own pathway began with volunteering at community legal centres, where he was able to understand the work and clients first-hand. ‘Getting experience in the community sector so that people are able to show their knowledge and interest in human rights-type work is the one critical bit of advice I’d give.’

On the academic side, Paul suggests taking subjects such as Succession Law or considering a start in Wills and Estates as a valuable entry point into the field. ‘There's a lot of work to be done in the area, and particularly with our aging population as well, there's more demand for that type of work.’

As for underrated skills to start sharpening now? Practical writing skills top the list. ‘I found a really steep learning curve when I started as a lawyer,’ Paul shares. ‘I felt like I became really good at writing essays at uni, and then after getting out of uni, I never had to do that again. Then it was all about letters and emails.’ To this day, Paul continues sharpening his writing skills through professional development sessions, refining his ability to write clearly and succinctly.

Chapter 7: The Road Ahead

Looking ahead to the future of elder abuse law, Paul notes that a nationwide register of powers of attorney has been under discussion for the past two decades. ‘That would be really useful in this space to make sure it's clear about who has the authority to make decisions for someone else.’

As for his own future plans, Paul isn’t looking for a career change any time soon. ‘I’m just keen to make as much of an impact on this area as I can.’

Would You Rather with Paul:

Accidentally wearing a suit to a casual event or jeans to a formal dinner? Suit wins. Atticus Finch over Elle Woods (he's more human rights-focused). Morning coffee or 3pm Coke? Both, obviously. In this Would You Rather episode, Paul tackles the tough choices – photographic memory vs mind-reading, group assignments vs oral presentations, and whether he'd rather win every argument but be wrong 50% of the time vs lose but always be right secretly. Spoiler: he's taking the wins for his clients anyday.